Communications provider Twilio suffered a phishing attack on 4 August. On Monday, 11 days later, messaging app Signal disclosed that some of its users have been impacted by the attack.

The incident initially appeared relatively minor, compromising a tiny proportion of Signal accounts and exposing only phone numbers—not private messages—to unauthorised access.

However, as more details have emerged, this appears to have been a highly targeted attack designed to gain control over the Signal account of at least one well-connected individual.

Here’s what the incident can teach us about security, privacy and third-party risk.

Is Signal Private and Secure?

Signal has built its reputation on providing a private and secure messaging service.

The app received a massive boost in users in January last year after WhatsApp announced changes to its privacy policy that would allow ad-targeting based on business-to-consumer messages.

“Privacy isn’t an optional mode—it’s just the way that Signal works,” claims the company on its website.

Signal’s privacy claims ring true compared to the most widely-used alternative messaging apps.

Together with WhatsApp’s controversial “commerce features” around business accounts, competitor Telegram does not provide end-to-end encryption by default.

Unlike WhatsApp and Telegram, Signal uses “Sealed Sender” technology designed to mask metadata. WhatsApp currently faces a fine from the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) around how it shares metadata with its parent company, Meta.

But Signal, WhatsApp and Telegram share one crucial similarity: each platform requires users to register a phone number. This requirement ultimately led to Signal’s data breach.

Twilio Phishing Attack

Twilio is a US-based company that provides communications and authentication services. Signal contracts with Twilio for its phone number verification process.

The Twilio incident resulted from a “spear phishing” attack, a type of social engineering targeting specific people—in this case, Twilio employees and ex-employees.

Twilio described the attack as “sophisticated”—a term that has become something of a cliche across the blog pages of companies that have fallen victim to phishing.

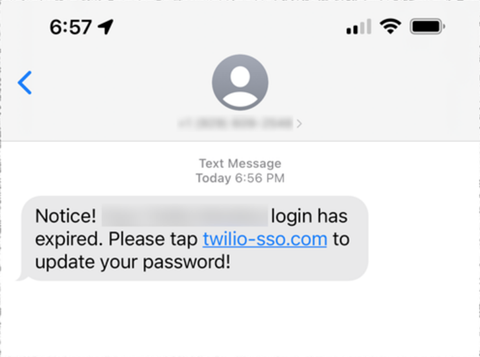

Here’s an example of one of the text messages Twilio employees received:

Note the URL, which includes “twilio” and “sso”, but does not refer to a page operated by Twilio itself. Instead, the link leads to a fake site that was set up by the attackers to imitate Twilio’s sign-in page.

“This broad based attack against our employee base succeeded in fooling some employees into providing their credentials,” Twilio said.

What’s notable about this attack is not the level of sophistication but that it was relatively unsophisticated—and yet it still succeeded against the (presumably) tech-savvy employees of a company that specialises in account security tools.

This underlines the reality that any company can fall victim to social engineering attacks.

“No training package (of any type) can teach users to spot every phish,” reads a blog post from the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). “Spotting phishing emails is hard. Spotting spear phishing emails is even harder. Even our experts struggle.”

Once in possession of some Twilio employees’ login credentials, the attacker logged into Twilio’s “internal systems” where they accessed approximately 125 Twilio customers’ data.

Twilio reports that it has taken several additional measures to protect against future attacks, including “hardening” its security at “multiple layers”.

Twilio also notified Signal, which then began its own investigation into the possible impact of the attack.

Signal Attack

Signal announced on Monday that around 1,900 of its users had been impacted by the Twilio attack.

Signal reported that the attack only compromised people’s phone numbers and SMS verification codes. Messages, contacts, profiles and other information remain secure.

This is a relatively small number of phone numbers given that Signal has tens of millions of users. However, given this brand’s reputation for privacy, those users may include people who have a particularly vital need to keep their use of Signal secure and confidential.

Indeed, the attacker reportedly searched for three specific phone numbers. One of these numbers, it was revealed on Thursday, belonged to Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai, a cybersecurity journalist at VICE’s Motherboard publication.

During the time that the attacker had access to Twilio’s internal systems, they were able to re-register Signal accounts to new numbers. This would enable them to send and receive messages from these compromised accounts via Signal.

This is what happened to Motherboard’s Francheshi-Bicchierai.

“The hackers were able to take over my number on Signal for a period of 13 hours,” he wrote in Motherboard.

Signal provides a “Registration Lock” feature to prevent unauthorised re-registration of accounts, but this feature is “off” by default. It appears that Franschesci-Bicchierai had not enabled this feature at the time of the attack.

It’s not yet clear who, if anyone, the attacker communicated with during these 13 hours via Francheshi-Bicchierai’s Signal account.

But during that time, a cybercriminal was able to impersonate a trusted, high-profile cybersecurity journalist who is presumably in regular contact with hackers, security professionals and public figures.

Phishing and Third-Party Risk Management at #RISK

The Twilio and Signal incident raises many important questions:

-

While security awareness training can never eliminate the possibility of a security incident, were Twilio’s employees sufficiently well-trained in recognising the signs of a social engineering attack?

-

Twilio’s security measures were evidently insufficient to prevent further harm once the attacker breached the company’s systems—what could the company have done better?

-

Should Signal, according to the principle of “data minimisation”, have required users to register a phone number to use its service?

-

According to the doctrine of “data protection by default”, should Signal’s “Registration Lock” feature be turned on by default?

The themes of data protection, social engineering, and third-party risk management will be covered in detail at #RISK, an expo at the ExCeL, London on November 16-17. Register for free below.

No comments yet